The Cornwall Project

Stuff tastes good at Coombeshead.

In one sense, that’s a piece about the place done with – it’s hard to imagine anyone who enjoys things that taste nice making the pilgrimage to Cornwall and finding fault with what is presented to them. Everything looks gorgeous; ingredients are combined and served with such bright, breezy judiciousness that eating there still feels refreshing even after three consecutive meals featuring things that could otherwise sit on a stomach like guilt: cheese, pizza, lardo, sourdough, butter, cheese, duck, cream, cream, cream, cheese, sourdough, butter, sticky buns, bacon, sausage, sourdough, butter, mutton, cream. It all tastes really, really good.

But it also tastes really, really good, in a way that makes you feel and question things about food as a category. To taste Coombeshead’s bread, or the various things made with local dairy – to enjoy the marvellously unfussy things Tim Spedding does with meat from the area – is to discover depths of flavour and richness that seem to belong to a different era, or a different planet. Stuff at Coombeshead doesn’t just taste good, it tastes better.

Which is a slightly uncomfortable realisation. In recent years – thanks in no small part to books like Ruby Tandoh’s Eat Up! – it seems that something is starting to shift, that people are accepting that food has no inherent moral value, that is not bad to eat cake rather than kale, or fast (ahem, “junk”) food rather than dry-aged single estate heritage breed forerib. All this I believe, so there’s something disquieting about experiencing this slow, careful, local, non-commodity food and having your world ever so slightly recalibrated by it. There’s a fine line between things like this tasting better and a more general politics of assumed superiority; as that interview with Ruthie Rogers made pretty unambiguously clear, it’s a non-distinction that can exist at the heart of projects that make ingredients their raison d’être. Think of the urban legends of young chefs being sent to Harrods to stock up on ingredients in The River Café’s early days: endeavours like this can come to fetishize bestness; can convince themselves into paying and charging whatever premium it takes to attain bestness and the perceived halo of moral quality it bestows upon those consuming it.

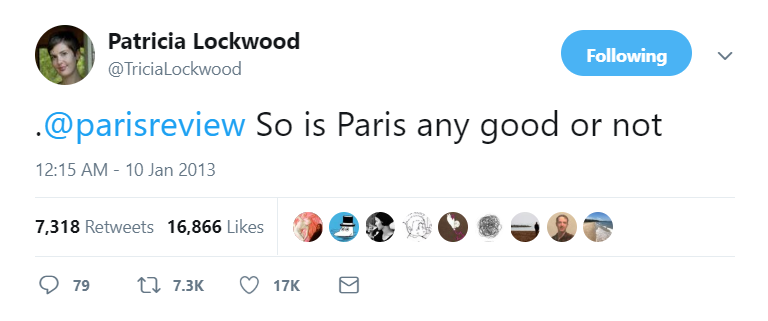

It’s not like that at Coombeshead. There’s earnestness and passion, but they’re not turned to proselytising; there’s a drive for quality, but given the economics involved, sourcing is necessarily resourceful, not motivated by an at-all-costs drive to buy the best. The décor isn’t twee, Londoners play-acting “countryside”; it feels organic, and tasteful – choices seem to have been made in order to bring you pleasure, not because they make for a sick ‘gram (one side-effect of this: everything makes for a sick ‘gram). There’s not a jot of smugness on show; there’s none of the coded snobbery you occasionally find in London – there’s just warmth, and humility, an almost cultish sense of blissful shared purpose. Cornwall is paradise, and the team are so, so excited to show you what their larder has to offer.

Two-ish years since opening, the food at dinner still feels excitingly like a work in progress. Big name sort-of similar projects are clearly a source of inspiration: Blue Hill at Stone Barns definitely features, echoed in a snack pizza-slice topped with various seasonal goodnesses. Ditto Noma, in a cutesy, ever-so-Vegetable-Season flower bouquet smeared with curd and nut butter. Both of these, along with a darling little Stithians cheese tart and gnocco fritto draped in house lardo, are taken in the garden in the sort of evening sunshine that photographers might kill for; it’s a short walk down to the dining room proper, housed in a converted barn.

More substantial snacks follow: bread, butter, ferments, a coarse terrine, honking with offal. Given Tim Spedding’s past, it’s no surprise that there’s a hint of The Clove Club in the protein-oblong-sauce-quenelle-Edenic-leaf-garnish geometry of the duck main course or in the ancillary “second serves” (hmm @ that term) that accompany it; nor is it odd to find whisper-echoes of P Franco in certain dishes and in the championing of old-school puddings (this is a man, let’s remember, not averse to the occasional Whim Wham). But there’s thrilling evidence, too, of an emerging sensibility that’s idiosyncratically Coombeshead, purely Cornish: in the brininess and juice of Porthilly oysters or the thickness of a chamomile pannacotta made with local cream. Those oysters are perhaps the highlight of dinner – swimming in dashi-esque broth (made not with tuna but with dried scallops), accented with tart bursts of lovage and the heat of shaved horseradish. Like that terrine and that panna cotta, they bring pure, unimprovable pleasure.

But as nice as dinner is – and it is very nice indeed – and as deservedly celebrated as the breakfast the next day may be – and it really does deserve your time and appetite, not least the sausage and some divine (and underrated) sticky buns – perhaps the definitive summation of the Coombeshead experience is Sunday lunch. Ours starts with more sourdough and more butter, plus snacks: some cod’s roe and cucumbers; pickles; a cheesy panisse. Then a leg of mutton, cooked à la ficelle over the kitchen’s open hearth, left to rest and sliced into satisfyingly rustic tranches. With it, some sausage and belly, a dab of shoulder cooked to the point of total surrender, and some charred onions. Plus sides: new potatoes, a garden salad, charred and chopped chard. Everything is just on point: picked right, seasoned right, cooked right. It’s a hot day; we’re only a couple of hours removed from breakfast. And yet we (I) eat and eat, in a kind of trance; it’s too good to stop. When it is gone, they bring a fool: rhubarb and red gooseberry, topped with a lovage and bracingly tart apple granita, condensation beading the glass. It is a perfect pudding to end a perfect meal, perhaps all the better for not carrying the weight of expectation that the previous evening did. Dinner doesn’t feel like a full chef’s tasting menu – it’s served with far less pomposity than that – but is still close enough to one in format and repute to drag the food nerds in from far and wide. Perhaps they come expecting the UK’s answer to Fäviken – an isolated hermitage where a chef-genius produces dazzling improvisations on the theme of rusticity, all the while maintaining a Michelin inspector’s eye for detail and quality control.

Coombeshead ain’t that. It’s just Tim and a sous and a stagiaire, in a big old room with a fire and a long kitchen table and a few bits of speciality kit. The food they produce is wonderful – it is pretty and thoughtful and clearly the work of people with exceptional talent, but it is first and foremost comforting. Sunday lunch is Coombeshead in miniature because this is where the comfort and warmth come through most clearly: it is entirely without affect. It’s just very nice things, served immaculately by people whose care for what they’re doing and joy in doing it shimmers in every gesture. Stuff at Coombeshead tastes good, sure. But that doesn’t begin to cover what makes it so special.